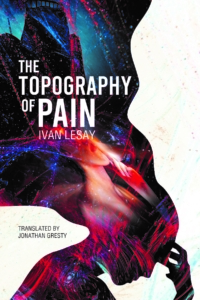

Part critical portrayal of life in present-day Slovakia, part sobering look at the country’s recent past with the euphoria of the Velvet Revolution replaced by growing cynicism, and part chilling depiction of a dystopian future, Ivan Lesay’s ambitious debut novel deftly switches perspectives, letting the reader guess the relations between its three protagonists: the beautiful student Naďa, the aspiring journalist Jaro, and Adam, a young man who falls down to earth from dizzying technological heights.

Julia Sherwood, translator, United Kingdom

Usually we don’t know the past, we don’t understand the present and we don’t dare to imagine the future. But Ivan Lesay knows and understands and he also dares to imagine, when in his extraordinary triptych he takes us on a journey through time from communist Czechoslovakia through Slovakia’s transitional present to the futuristic world of tomorrow, in which people can finally live out all their fantasies, precisely those that the past forbade and persecuted, and the present promised their fulfillment, only to cruelly crush its promises. The Topography of Pain is a surprising narrative about the worlds of yesterday, today and tomorrow, a brave writing odyssey by a talented writer that demands an equally brave and talented reader.

Goran Vojnović, writer, screenwriter and film director, Slovenia

Editor’s notes on the margin of Ivan Lesay’s debut Topography of Pain

It often occurs to me that it doesn’t do a writer any good to just be a writer, to be too wrapped up in oneself and the craft. Then he starts writing about writing, fragmenting the form, inventing metajokes, and all of this is still possible if he doesn’t lose sight of the fact that this is one of the possibilities and not a necessary outcome of contemporary art. Many of our contemporary artists have no such self-reflection.

If the three stories in Ivan Lesay’s Topography of Pain are all believable despite their diversity, if his three heroes are as full-blooded as they are full-blooded, perhaps it is because Lesay is not an artist by profession. Perhaps the news has not yet reached him that the author is dead, that the story has survived, and that introspective prose is the order of the day. He has not resigned himself to the possibility of a statement that would have wider validity, nor does he reflect the decay or loosening of values in a decayed or loosened form. He is a storyteller as we know (and like), and he reflects the state of the world through story.

A few years ago, in a short series of articles for Salon, the Thursday supplement of the daily Právo, the Czech critic Eva Klíčová reflected on whether our way of perceiving literature is not actually already outdated. We used to separate junk (recreational, consumerist work) from quality literature (i.e. stylistically sophisticated and richer in meaning), and critics, of course, only focused on the quality literature. What if it no longer makes sense? Shouldn’t the elite move „to the second floor“; couldn’t quality also be comprehensible, accessible? Lesay’s book is, I think, a noteworthy step in this direction.

Naďa, the protagonist of the first novel, is forced by an unexpected diagnosis to revise her life, and Naďa eventually takes a rather radical approach. Lesay writes engagingly, almost sensationally, the text at times smacks of so-called women’s literature, but at the same time the superstructure of meaning, the contradiction of ideas, is never completely lost. The second novella, Jaro’s story, is stylistically more restrained, but once again we are dealing with a sophisticated character whose (on the surface, perhaps dubious) decisions are not evaluated, but rather problematised. Finally comes Adam, and this third novella, in its own way, again delves into genre practices (science fiction), even this time without major qualitative concessions (stylistically, it returns to the initial exuberance, and even intensifies it, the language at times already seeming to outgrow itself). It is possible to write both intelligently and engagingly.

I don’t want to over-praise, I don’t love the book unconditionally, and there were some points where Lesay and I disagreed while working together. But at the same time, I was very glad that there were places where he stood his ground and was able to argue his point (after all, I guess that would have been tragic, an artist with no opinion and no will), and the book was and is close to my heart, regardless of my reservations. I don’t want to think of books that way, but for a time, when the work was at its most intense, I wondered if Lesay had done something I myself had attempted in my last prose work better. There is probably no objective „better,“ of course; we just approached the same themes in different ways. Either way, Naďa’s reflections on the body, her struggle to come to terms with it and dwell in it, her reflections on what defines her as a person, and Adam’s raging impenetrability and empty hands, the uncertainty of identities and the need to lean on something external, all of this speaks to me immensely, artistically and humanly. Certainly, one might note that these themes are perhaps timeless.

Strange that Lesay could fit so much into the text. I keep thinking that just as we can read The White Whale as an adventure story and ignore the allegories, Topography of Pain can also be devoured as a collection of genre fiction, the philosophy need not be ignored. Philosophy, that sounds dusty! And maybe in both cases the story is the pink coating, the added sugar that makes it easier to swallow the pill, and then the thought content is somehow subliminal..

I’m excited about the book being published in Ikar, too. I understand that there is a huge amount of original and foreign work coming out every day and we are all looking for some clues to orient ourselves, but it is important to remember that these are just landmarks and not independently functional criteria of quality. It’s not going to be the crème de la crème of a publisher’s portfolio just because it’s small and lives on Arts Support Fund grants. In the same way, Ikar isn’t just cheap romance, naked dukes and Grisham thrillers. I’m under no illusions that one book could make a difference; on the contrary, maybe even Lesay will be overlooked by reviewers or too quickly pigeonholed just because of where it came out, but it’s still a good thing – Ikar surprised and gave a chance to an unusual debut, maybe some critic will surprise, too, and give Ikar a chance.

It’s hard enough to write about a book I’ve edited, especially since it’s actually quite fresh. I’ll make it easier on myself by going into the admitted field of subjectivity. I’ve read Lesay’s text many times, and there are places in there that I still wrinkle my brow a bit over, and places I love. But the one closest to me has always been Adam, and especially his relationship with Inge. There’s something both beautiful and agonizingly tender about it, something that touched me the first time I read it, and perhaps deepened the next time I read it.

Moments like that might justify the whole book to me, if it were weak. And from such a critic should disengage, so that – I’m almost tempted to say that perhaps it’s not even the criticism that matters – but the fact that there are enough readers who will find such a place. Yours. Time will tell.

Topography of Pain is a strange text, more powerful than the story is the atmosphere of confusion, a kind of constant sense of loss of the meaning of existence. It’s a text you wouldn’t want to live in, because none of the characters have happiness and goodness in their fate. And yet we are drawn to it because it speaks to our lives recently, now, and in the near future. We met Ivan Lesay for tea in a bookstore.

An economist, a financier and literature, two quite different worlds. Why did you decide to write?

I’ve always enjoyed literature as a reader. And I had this dream that one day I would write a book. But for a long time I thought it was impossible because I took a different career path, which I also enjoy very much. But then I started actually inventing bedtime stories for my daughter, and I started writing the book actually for her. The fact that it got published was just a plus. And that started me thinking that I could actually write an adult book as well.

But economics, finance, political science, these are exact and serious subjects. And the fictional world is much more about fantasy and invention, isn’t it? Is that an escape for you?

It’s kind of related, too, because in economics and political science I was and am involved in observing society. Trying to name what’s going on. But I find the means of science to be somewhat inadequate, or the academic language very precise, exact, there are formulas and structures. Unless one wants to be an academic know-it-all, one has to specialize in some part, some slice of knowledge. And that tied me down. That’s why I wanted to formulate my vision and perception of the world somehow differently. And personal stories can be exactly a way of saying a lot about society and its vision as well.

Your novel is inherently realistic, although one of the stories is a vision of the future. But it is more about the moral state of the last thirty years. Have we fallen into a human and moral crisis in the formation of the new state?

You put it precisely. I have been looking at the process of transformation of Central Europe and, in it, Slovakia in recent decades. But I was aware that it was a fascinating time. We take many things for granted today, but the transformation was enormous and not everyone can say that it was successful for them. What I missed to some extent was the attempt to grasp the era artistically, as, for example, Peter Pistanek and his Rivers of Babylon grasped some of the transformation. I was greatly helped by the American historian James Krapfl’s book Revolution with a Human Face, which looked at the history of our gentle revolution „from below“, i.e. through the eyes of the people on the street. Ordinary people often see history through their own personal life stories, and it’s a different history than the „big“ ones, the political ones. And out of that the stories were gradually born, first actually the story of Jaro, who is chronologically the first, although second in the book, then the story of Nada from the present, and then a kind of visionary view of Adam was formed in the third story of how society might actually evolve.

The reflection of history in your human stories also speaks to the fact that we live in bleak times.

Social reality has a powerful effect on everyone, we cannot avoid it. My original naive intention was primarily to write about the times and use the stories of individuals. But then the characters started doing what they wanted and I was surprised to find that other authors‘ words were confirmed – the characters came alive. Until I forgot the original intention and let myself be guided by their lives. But that time, the view of it, stayed in the book in the end. And I’m glad that the first readers did find what I originally wanted to put in there, which was the naming of the time you’re talking about. It’s a story about the transformation of a regime, but it’s also about the transformation of people and the fact that not everyone is a winner.

The 21st century has made us free, individual, but also unhappy. We live in a hyper-consumerist age, but we seem to lack humanity and a sense of being. That’s what I feel from your novel. Do we lack a sense of life today, a vision?

I’d like to believe that no, it’s not missing, but I’m not sure. Maybe the meaning of life is too big a word; I’m telling stories of people who maybe have a problem with their own identity. Society is fragmented today, we have no identity and it may be even worse in the future. Freedom is great, but we see free people – the first of my characters has huge ideals and stumbles upon the ordinary reality of a post-communist country. Naďa had no ideals, but her illness puts her in a situation to survive and she chooses perhaps to the extreme. And Adam, in turn, is a man out of the context of his new times. But I believe, despite the marasmus, that there is a point in trying and looking.

But literature can also be a warning we are missing certain layers in society. On the literary side, I must say that your text is very sophisticatedly written. What is your favourite reading?

I am a vivid reader. At home, I read explicitly only fiction. I like Zadie Smith, for example, but I also like psychological crime novels by the Irish author Tana French, and from Slovak authors I am interested in Alexandra Salmela and her Antihero or Mika Rosová, Zuzka Kepplová, Mišo Havran.

Your narrative is also more of the kind of literature that requires the reader’s cooperation and intellectual attention as well. Are you playing with the reader? Do you want him to read attentively?

It’s my first adult book, so I don’t know yet. But I like it when a book isn’t simplistic, when the author tries to say something more through the story, when some intellectual effort needs to be expended on the text. For example, I wrote the book in chronological order, only later did I actually switch between the first and second story. But I think a good book includes both the story and the appropriate level of difficulty. But that has to be discovered. I like the fact that during the quarantine, for example, my older daughter, 13 years old, discovered books and started reading. My wife, a psychologist, says that models and role models work more than any do’s and don’ts, so when kids see us reading though, it sticks with them.

Martin Kasarda

interview in Magazin o knihách (Magazine about books), supplement of the daily newspaper SME

One of the hallmarks of literature in recent decades, I think, is that it has lost the novel. Advancing modernity has led to fragmentation, the glamorously glittering shards of which have scattered over artistic expression as if in a desire to gloss over a perhaps unwanted paradox – that it loses the power of generational narrative with modern fragmentation. Ivan Lesay’s Topography of Pain, recently published by IKAR, is a novel in content and dimension. And since a testimony should have something to build on in order to be generational, the present here acts as a link between what will be and what we think and feel will come to pass.

The uninitiated reader, of course, has no way of knowing in advance that he or she is in for a near-epic narrative as a result. At first glance, even on the book’s flap, he sees three stories, three separate entities whose protagonists are always someone else: Naďa, Jaro, Adam. By immersing ourselves in the reading, we are plunged into the present, or more precisely, the last lived years of this millennium, a fact of which the story is very quickly convicted by modern technology. But not only that. The first chapter, or sorry, the story, is titled The Body with the addition (subtitle) of a pro-topia, which – for now – the reader has no reason to explore. The first topos on the map of pain is thus tied to the present and to the body in which our familiar present is lived by Naďa. Basically, such a normal story of a young woman with a somewhat vague, all the more „normal“ background: she is studying at college, living in a dormitory, changing part-time jobs and jobs, bored with her „inertia“ boyfriend, and oscillating between her beautiful and noble, but increasingly distant desires and dreams on the one hand, and the reality that forces her to accept the brutality of everyday life as the norm on the other. Of course she never aspired to become a sex worker, of course she enjoys a classical music concert rather than the hollowed-out world of internet anonymity; but how is a young woman supposed to survive with her sanity and keep her principles firm when the laws of predatory capitalism press down as mercilessly as the big belly of a horny drooling boss, and asking for help could mean sinking to an even deeper social bottom? How does one not go mad from the real face of the world, if not by accepting its rules? And then there are the details: a Czech mother who raised Naďa alone, an alcoholic father long gone but his talents left behind – he was a journalist, supposedly, and Naďa has his talent. She writes brilliant sex blogs under pseudonyms. „Dad, buried deep in the recesses of her subconscious… after all, after all that happened to him.“

The second story is called Tongue, subtitled u-topia, and in it we go deeper back in time. We’re in the late 80s/early 90s, agile communist cadres are turning into orthodox capitalists, some are committing suicide, everyone is terribly looking forward to freedom, which is being synthesized right before everyone’s eyes with hard currency and bird gods with free lips of a market as wide as the universe; we don’t know yet that they’re made of wax. Somewhere above Bratislava stands the journalist Jaro, refusing to accept the emerging reality. „Who do you think owns this city?“ his friend and colleague Boris asks him. The idealistic Jaro smells a perfidious whiff of the stench of opportunistic pigs flocking to the reigns of the „Western standard“ from his friend, who has taken up some undefined „provision of legal services“. „Houses, businesses, everything is shifting from one hand to another, the old order is collapsing. You see buildings, I see ruins. A city smashed to smithereens. Actually, it’s a pie. And the pie is going to be divided. Now the knives are being sharpened and the spoons are being cleaned.“ Oh, why hasn’t it just been clearer than the sun that for the vast majority of the new nomenclature, „freedom“ has exactly the same definition as mere philistine greed? Yes, it’s now clear from whom Naďa in the previous story inherited her writing talent and her unmooredness in a brutal world, and it’s also clear „what happened“ to her father after „all that,“ and why he became an alcoholic. It’s already clear that the stories in the book are not pieced together by generational divisions; it’s already clear that the third part will be part of this same, fragmented family in a fragmented history.

Its hero is Adam, the story is subtitled a-topia and entitled Mind. Now that we know that the book is actually a conceived trilogy, we expect it to be set in some other time. But which one? Could it go even deeper into the past, to the time of Naďa’s grandparents, or return to the collectivizing „demons of consent“ as a counterpoint to crude privatization? This is not necessary – we can make do with worrying about the future, suspecting the defects of the present time. And so Adam’s reality is the future, somewhat in the vein of dystopian science fiction, somewhat film noir, somewhat with the eyes of Eddie Constantine and Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville. Networked agencies, epistolary, lots of English, few accents, expressive with many „masters“, „global“ „rawballs“, and somewhere in the back, behind the virtual alienation and sexual crudeness as a subtle but persistent backdrop, a red thread of longing for love, for a simple earthy touch, for the connection of the disfranchised that sometimes emerges, for example, in the form of letters. This time from grandfather to grandson. The story of several generations comes to a close, the shreds converge… but it is still more a longing than a reality.

Reality is a bloody cut by shrapnel, on the topography of the pain of our last decades and future perspectives, utopia has been lost. Only later, perhaps, will the reader realise why utopia is associated with Jaro and not with his daughter Naďa, whose story the author has labelled a protopia. But what is protopia, anyway? According to the North American futurist Kevin Kelly, it is a reaction to utopia, which is merely „an unattainable fantasy.“ Although utopia is originally thought of as an ideal worthy of pursuing, even as it continues to recede from us, Kelly understands it as something that loses its meaning just as it ceases to recede, when it is achieved. On the contrary, protopia is a gradual and slow moving forward without the need to assimilate the structures established before us, to seek by force-power something new at a time when the newest can only be something time-tested. „The umbrella that helped me keep faith and hope in humanity“.

Ivan Lesay’s novel The Topography of Pain is an umbrella under which the pain of several generations has been hidden, but certainly especially the pain of a generation that was given the gift of the opportunity to experience the history of discontinuity for itself, but in the age of modernity’s shrapnel has still not given a coherent generational testimony. There is no doubt that this book, too, is only an attempt at coherence, an attempt at a true novel, an attempt to restore dignity and meaning to structure, to form, to those elements of traditionalism that we have not had and have no right to damn in the name of progress. But it is a remarkable attempt, and despite the deliberate and ubiquitous vulgarisation of sexuality, the pointing out of filth, disillusionment, coarseness, and indulgence in the remnants of the manifestations of prettiness, it is not really a mapping of the vulgarity we have succumbed to and which Peter Pišťanek used cynicism to describe in the early 1990s. The Topography of Pain is rather an image of melancholy, a sadness for missed opportunities; but this is because the author misses beauty, not because he pragmatically mocks it.

It takes talent and courage to write a decent book. Ivan Lesay has only one of these. In a short medallion, the author introduces himself as a political scientist and economist who has written a children’s book and had a short story published by Fraktál magazine. So it’s quite all right to consider him a debut author. In his book, he tries to present three reader-appealing fates that are only very loosely intertwined with each other, while all of them are searching for answers to the same existential questions. The characters don’t work out. And neither did Lesay.

The biggest problem seems to be the author’s indecisiveness, going to the point of excessive vagueness. The very first problem is the genre of the work. One can argue whether it is a novel with three long chapters or, and this is more likely, the author has written three novellas published in one book. This is suggested by the fact that each part has its own title (Body, Tongue, Mind – how original). Lesay thus wrote three novellas that contain one main character and many questions about the nature of existence.

Philosophizing is present throughout the book, but at times it is so shallow that sharp rocks of clichéd expressions and nonsensical rhetorical questions shine through the waters of endless pondering about existence. „How can people be so wasteful, ordering something they’ll only eat a bite of?“ appears on page 49, with the first novella’s main character Naďa describing her newfound love of music in the alleys of Munich, not the global predicament of food waste. The author puts thoughts into the characters‘ heads that should not be there, given their character and condition. He uses the characters as tools to present his own views and makes them puppets without believable character.

Most of the time, the author’s even a successful train of thought, which sounds justified in the character’s head, arrives with something mundane. He is fond of ending a meditation on life, for example, with self-serving vulgarisms that turn even a successful passage into a deflated balloon. The passage is thus once again only almost managed, almost believable, and almost readable without rolling one’s eyes. Lesay’s mixing of high and low is neither elegant nor necessary. Rather, it comes across as if his indecision is making a statement. He wants to write about the life of an unrepentant prostitute and inscribe high ideas in her head – clichéd, admittedly, but why nitpick, but then he obliterates those ideas with slang, vulgarisms and another layer of shabbiness. His will to seek answers to thousand-year-old questions is thus lost beneath a layer of uninventive language, and the reader is left to wonder where he has seen this before.

Speaking of that shabbiness, one can’t help but pick out a couple of brilliant examples: ‚the words rolled out of me like a waterfall‘ (p. 112); ‚How ridiculous and defenceless we come into this world. And, in fact, how ridiculous and defenceless we survive here, and how ridiculous and defenceless we die.“ (p. 70); „But was it really so? When I saw her there in the light of the sun setting over the Prague suburbs…“ (p. 224). In the shabbiness, unfortunately, it’s not just the lexis, the whole breathtakingly pathetic epithets or the most typical images in the vocabulary of an unoriginal writer.

The third novella, set in a dystopian future world, contains an enumeration of crimes against pop culture. Here the author rips off Kazuo Ishiguro, the Westworld and Black Mirror series, the dystopian Harvest of Death trilogy, and surely something else that my head, outraged by the chaos, failed to register. Because it’s exactly as chaotic as it sounds. The author didn’t specify what time span passed between Naďa’s and Adam’s story (Adam is her son), but given that the protagonist of the second novella, Adam’s grandfather, is still alive in the third novella, it’s safe to assume that it could have been fifty years at most, and even then only if I’m being really generous. Despite this short span of time, we suddenly have a very different world in the book, one that not only I didn’t understand, but apparently neither did the author himself, because he went from not knowing what else to add to it, out of the goodness of his heart, to not knowing what else to add. So Adam resolves his existential questions against the distant backdrop of a complicated future world in which people can encapsulate their minds, may or may not be real people, and may live either in the so-called underworld or in the real world, where buildings are newly constructed out of some kind of immaterial substance. I repeat, a maximum of 50 years has passed from the point we live in now. By the third part of the book, the author had completely lost control of his own creation, everything stopped making sense and his inauthority and indecisiveness were writing for him. The ending is even more vague than the previous two, which begs the question of what the author was actually proving to himself. That we will never get answers to those philosophical questions of his existence? That we may get them, but he refuses to write them down explicitly in the book, and thus give them away? That he hasn’t the slightest idea what he was proving? The third answer seems to me the most appropriate.

Ivan Lesay’s courage is not lacking. He began with a story about a prostitute that leans dangerously towards the stereotypical overuse and contains largely inexplicable brackish passages. He continued with a novella that almost made me forgive him for the first one, because it’s simple, elegant, and finally at least somewhat credible, but then he skipped on with grace. Unfortunately, the gracefulness was not reflected in the portrayal of Adam’s story, which reads like an ordeal. For the author to write it, for me to read it. The Topography of Pain in his views, rather than in his philosophy, reflects the feelings of the reader, who undoubtedly feels some of that pain, physical or psychological, as he buries himself in the text. In my case, unfortunately, it was not physical at all.

Adéla Vojtušová

Rozum magazine No. 3/2021

A-KO-ŽE. Lesanka's Fantastic World

Karol Sudor said on Pista Vandal that the Christian-metalist is an excellent PR. With Ivan Lesay, the Secretary of State-metalhead, it could work too.

Tublatanka, Doctor Alban, DJ Bobo or how to make mums laugh

I like to see some author strategy behind the text of a children’s book. You can feel it really strongly in Lesanka. And there are several of them. There is, for example, an obvious attempt to win over female readers, for example, with jokes that are clearly not intended for children (the gym boys are said to be devouring protein shakes; at the fair, the dentist Doctor Alban talks about his life; at other times, Tublatanka or DJ Bobo win again). Lesanka’s dad as narrator tends to self-mock (like Janovic’s Wooden Dad). He admits to being outrageously lazy, especially when Formula1 is on TV, he lies, thinks only about when he’s going to have a beer, and often loses track of what’s going on with the kids because of it.

More than one mom will say to herself that it looks the same at their house. Another between-the-lines joke reserved for moms: in the chapter where Lesanka and her friend are kidnapped by a group of slave-owning Vetroplachs and want to turn them into slaves, the girls realize that as slaves, they’ll have to cook, wash, iron – do all the things that moms do. The book is said to have been written by Lesanka and her dad, friends and mom together, and is best read that way – in parent-child tandem. It’s great that this trend of family fun, which has worked well for movie fairy tales, is being tried by children’s book writers too.

I and kids also really liked the author’s sense of language. He creates witty new words with ease, playing with names and homonyms (a crate of gin turned into a well-meaning genie who grants all wishes). Some of his innovations have even made their way into our family dictionary. Although the author is not a writer at all, the stylistics never flag anywhere.

What we can envy the Lesay family

The genius Philip Roth taught me not to voyeuristically search for how much of a text originated in the author’s life. But with the book A-KO-ŽE, I feel like it is exactly what it pretends to be. The shared fantasies of an entire family, written down once by Dad, once by Lesanka, once by her friends (the chapters are called From Lesanka’s Dad’s Notebook, From Lesanka’s First Writing, From Lesanka’s Dad’s Computer, From Lesanka’s Second Writing, …). All of them are first based on a real situation, which at some point switches to a crazy situation – the characters suddenly find themselves in the fairy-tale land of Lesankovo (just like in Bambuľkovo, the rules here are quite different. For example, the girls easily beat the boys even if outnumbered).

Lesankovo is in no way locatable geographically or temporally, rather it is a state of mind where nothing is impossible. Everything that girls aged 7-10 are interested in is here: animals, clothes and the world from centuries past, witchcraft or even thinking about the meaning of life, death and life after death. Lesanka’s stories are so wild that they were probably really largely made up by the author’s daughter and her friends, to whom the book is dedicated. If the creation of this text really took place in this way, as a collective family process, then we have much to envy the Lesay family and much to take inspiration from them.

The construction of the mini-stories – silly twists and turns at a frenetic pace – is the toll of being co-created by an unbridled child’s mind. But the child audience certainly won’t complain. The tighter the plot, the more my daughter laughed. Although not all the chapters are equally heartfelt and funny, she clamored for Lesanka every day until we conquered this nearly 100-page book. Here’s an excerpt from the first chapter, where the main character and her father fall asleep and suddenly find themselves in a strange land:

On the way, Lesanka and her dad were wondering how to disguise their pyjamas so they wouldn’t look like patients on the run from the hospital. Fortunately, in Lesankovo, with a little imagination, it is easy to outwit or fool someone – that is, to disguise oneself. As soon as they reached a nearby vineyard, they saw two scarecrows in discarded jerseys of the local football club. One was quite a bit smaller, probably junior league, and stood straight up in a molehill. But at least he had a bright red cap. The faded shirts, originally green in colour, and the washed-out blue shorts billowed like a corner flag on them. Daddy and Lesanka looked at each other playfully and exchanged outfits even more enthusiastically than football players do after a game, because they don’t change their shorts. Even the schoolboy jersey still hung on Lesanka like a dress, but otherwise they were fine. The straw men, on the other hand, looked quite intimidating even in their pyjamas.

Lesanka in psychiatry

The nonsensical plot hides beneath the surface the author’s reflection on the crossing of the boundary between reality and fantasy. What induces other states of mind? Falling asleep, an accident, alcohol, a traumatic experience or just plain dreaming with your eyes open. In the last chapter, through the mouth of a chief psychiatrist, the author explains that there is no boundary between reality and dream, between normal and abnormal, that people are both what they really are and what they are in their fantasies. In the context that the narrator’s (author’s) wife is a psychologist, this is not a trivial statement. Our brains really do process the stimuli of our imaginings in the same way as if they really happened.

In this last chapter, Lesanka, her friend Pinelka (a reference to the Philippe Pinel Psychiatric Hospital in Pezinok) and Lesanka’s mother are taken to a psychiatric ward, even though they feel they are the only normal ones in the whole strange Lesankovo. In this story, the gateway to Lesankovo becomes a mirror – again, surely an allusion to the psychiatric quasi-mirror from behind which the patients are observed. The author has managed to sneak all these heavy themes into the book in such a way that they do not disturb the child reader in any way.

Illustration

You will recognize Petra Lukovicsová’s black and white figures at first sight. In addition to A-KO-ŽE, she has illustrated the book Journey to the World, the album My Family Album, and the newly published book Emotions in the City; her illustrations have appeared in Slniečko and in newspapers. This time she has added collages to the mischievous characters, so the illustrations are more colourful. They’re drawn on lined paper with margins – all of which adds to the feeling of authenticity (as if the stories were really lifted from Lesanka’s notebook).

Who is the book for?

Kids who have grown out of peaceful fairy tales and are looking for something more action-packed. Because things happen in Lesankovo! Girls are using grenades to fight the insidious slaver Vetroplach, schools and nurseries are being bombarded with ice cream from a flying carpet. It’s still a children’s, fairy tale world, but already with a hint of adult themes, so I’m guessing for the 7 – 10 year old category.

I recommend reading it with your kids though – sometimes they need some explaining, and not just retro Doctor Alban type stuff. Plus, there is copious drinking of alcohol throughout the book. At first I didn’t mind, but when not only Lesanka’s father was drinking, but the horses and even the baby got drunk, I censored those passages as a precaution. Indeed, alcohol is mentioned in every chapter, so making it the leitmotif of the whole book was the author’s intention. There’s definitely a message in there for parents to not take parenting so seriously and instead let themselves be swept away by the crazy fantasy of children’s games. It is also a message in the sense of carpe diem. After all, alcohol is just an adult parallel to the crazy games and dreams of children. The self-censorship we turn off with alcohol is just cultural accretions. You can experience how much easier life is without them with Ivan Lesay and his Lesanka. Or with your own children .

Do you have this book at home? How did you like it? Or do you have any questions? Leave me a comment.

The book was published in 2016 by Trio Publishing. It has 96 pages and a size of 168×230 mm. If you liked this review, you can buy the book here.

"Happiness happens slowly and quietly. So enjoy it," says Ivan Lesay

My guest on this episode is Ivan Lesay. Ivan is a senior climate finance advisor at the National Bank of Slovakia and has served as the State Secretary of that country’s Finance Ministry. In addition to his policy work, he has published two children’s books, and writes lyrics for a hardcore band. His debut novel for adults, Topografia bolesti, was published in 2020, and was shortlisted for the Slovak National Book of the Year award. An English translation of the novel, The Topography of Pain, translated by Jonathan Gresty, was published by Canada’s Guernica Editions in 2024. In its review of The Topography of Pain, The Miramichi Reader said that “Lesay is comfortable with data and figures, no doubt; he’s also gifted with words.”

Ivan and I talk about the (mostly) friendly rivalry between Slovaks and Czechs, and how that parallels Canada’s relationship with the US, about suddenly adding a side-career as a novelist to his distinguished work in economic policy, and about how, thanks to COVID, his novel never got a proper launch event until the publication of the translated version last year.

This podcast is produced and hosted by Nathan Whitlock, in partnership with The Walrus.

Music: „simple-hearted thing“ by Alex Lukashevsky. Used with permission.

Gešo in Pena dní_FM welcomed Slovak author Ivan Lesay. His novel The Topography of Pain was recently published. Listen to the recording.

(from 43:20)

„Today’s third news is a novel by political scientist and economist Ivan Lesay. It’s called The Topography of Pain and it tells through the life stories of Naďa, Jaro and Adam the impact that historical events have on the lives of individuals – whether they live in the present, in the past – in the former Czechoslovakia or in the future Europe. It is a book about how three blood-related characters perceive their own identity.

The first character is a young student, Naďa, who, after a series of low-paid jobs, earns a living from sex work and writes a blog about it. The second character, Jaro, is her father, who left the family when Naďa was quite young, and Adam is her future son.

The Topography of Pain is readable, very decently written, and there are a number of interesting insights that sometimes overwhelm the story itself a bit. In any case, a book that deserves attention. An excerpt from The Topography of Pain by Ivan Lesay will be read to you by Dominika Žiaranová.“

Ivan Lesay, a native of Trnava, is a Slovak political scientist, economist and publicist, but he interests us as a writer. In addition to his popularization book Life on Credit, he has also written a children’s book called A-KO-ŽE. Most recently, he has also added a book for adults, The Topography of Pain. Jana Hevešiová will now talk to him about it.

Listen to the recording.

The second hour of the Tuning Special from 15:00 was accompanied by Pavol Náther.

Martin Kasarda: Land of Beautiful People;

Ivan Lesay: The Topography of Pain;

Richard Brenkus: SATAMARANGA;

Rastislav Puchala: Ark of the Covenant.

An interview with writer is also included Diana Mašlejová.

The Topography of Pain is a thought-provoking and introspective novel that delves deeply into the human experience of suffering, both physical and emotional. Lesay combines elements of personal reflection and broader philosophical themes, offering readers a unique exploration of pain’s impact on the body, mind, and soul.

The narrative is heavily reflective, centered around a protagonist’s grappling with trauma and physical pain, perhaps symbolizing the existential weight that many carry through life. The novel’s title suggests that pain has a geography of its own, with different forms, intensities, and durations that mark their own territories in the human experience.

Lesay’s writing is often introspective and meditative, likely to resonate with readers who appreciate literary fiction that doesn’t shy away from uncomfortable or difficult topics. The book’s pacing can be slow and contemplative, demanding attention and patience from the reader, but for those willing to engage deeply, it offers a rich, emotional experience.

Although The Topography of Pain may not be an easy read for those looking for action-packed plots, it speaks to those who enjoy literary fiction that invites deeper thought about the human condition, the nature of suffering, and the ways we navigate and internalize pain.

If you enjoy books that focus on existential and emotional depth, this novel might offer a meaningful experience. The philosophical undertones and exploration of trauma make it a powerful read for those interested in how pain shapes lives and the ways people confront it.

However, the novel’s reflective nature might not be for everyone—if you’re looking for a plot-driven or fast-paced book, this might not meet those expectations.

Once upon a time there was a land where an authoritarian regime held sway over the nation. But one day revolution ignited, and the system broke down. The country broke in two. The people broke in pieces. It hurt, and the pain endured as they started searching their path forward, some striving valiantly, others less so. The Topography of Pain unfolds as an intricate narrative that delves deep into the torment spanning three generations, unveiling its myriad facets, whether surreal, hyperrealistic, or postapocalyptic. At its culmination stands a man named Adam, who has the chance to cut the chain and bring himself, the family, the country back to the joint. In the end there is hope.

Alexandra Salmela, writer, Finland

Someone who just wants to be left in peace is being hit hard by destiny and biology. Ordinary people have extraordinary lives. Periphery happens to live the very essence of the history.

Is it because of the time and the place? Generation between two eras, country between the big worlds. All kinds of division here! Plus lots of love and alcohol, very naturally present.

Jānis Joņevs, writer, Latvia

“ Topography of Pain is a shattered masterpiece. It does for our increasingly fragmented social reality and personal identity what Kafka did for labyrinthine bureaucracy. It’s existential literature for an era with no unified existence, just shards of glass from an exploding funhouse of mirrors, out of order, leaving only slices that reflect encounters and moments of humanity while cutting across three generations. It’s not hopeless—within those reflections, Lesay leaves us a thread to connect the pieces—but it is a direction and a warning. Like the very best literature, the rest is up to the reader.“

Alexander Boldizar, writer

From 1976 to 1983, Philip Roth edited “Writers from the Other Europe” for Penguin, a series of 17 books by writers from behind the Iron Curtain. The purpose of the series was to introduce new literary voices to Western audiences — voices emerging in circumstances vastly different from their own.

Most widely remembered now, among the chosen writers, is Milan Kundera, who captured the absurdities of life under communism in his novel, The Joke (1967) and later popularized the erotic and intellectual possibilities and risks of the quest for freedom in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984).

In the Communist Era, writers were forced into the labour workforce as captured in Ivan Klima’s 1986 novel, Love and Garbage, about a writer turned trash collector, a novel banned in what was then Czechoslovakia until after the 1989 Velvet Revolution. This peaceful revolution, which brought the Communist Era to an end, forms the distant backdrop of Ivan Lesay’s 2020 novel, now translated into English by Jonathan Gresty, The Topography of Pain.

Communism may be gone, but Lesay’s novel follows in the tradition of the “Writers from the Other Europe” series, showcasing a new literary voice who has emerged from circumstances different from our own. The 1989 revolution saw the release of much optimism – yay, freedom! – followed by the collapse into a confusion of dashed hopes. The 2008 global financial crisis compounded the despair. Where the West had once offered dreams and moral clarity, this new world offered a tough road to hoe.

Lesay has a PhD in political science and from 2015–2017 served as the Slovak State Secretary of the Finance Ministry. He contributed to an essay on “Political Economy of Crisis Management” published in the Europe-Asia Studies journal’s special 2013 issue on “Transition Economies after the Crisis of 2008.”

Lesay is comfortable with data and figures, no doubt; he’s also gifted with words. In The Topography of Pain, he has told a story of crisis management in the form of three interwoven stories. One takes place post 1989, one takes place in contemporary Slovakia, and the third takes place 30 years in the future. The three time periods focus on three members of a family: a father, a daughter, and a grandson. Each of them exists in deeply unstable worlds.

Though the instability is different for each of them, readers are drawn to connect the dots. For each generation, there is crisis; in some ways it is the same crisis. Each one struggles to make the best of it. We are not far here from Kundera’s joke or Klima’s trash collector, except the ideological and economic system is capitalism now, not communism. How to live? How to survive?

The novel consists of three parts, one for each time period and character. Within each section, time is fragmented, which can make for a challenging reading experience. After a while, the events form a collage in the mind and the connections are understood to be more intuitive than logical. The invisible hand behind it all remains a mystery. One is reminded that what Kundera found unbearably light was related to Nietzsche’s theory of eternal return, the idea that history is a cycle that will repeat infinitely. Carry on.

Michael Bryson, reviewer

In this interview, Esoterica’s Leah Eichler chats with Ivan Lesay, author of “The Topography of Pain,” his debut novel that was just translated into English and published by Guernica Editions. The book is written in fragments, keeping readers on their toes, and tackles issues such as sexual morals, ethics and capitalism in post-communist Slovakia. The interview covers Slovak literature after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Canadian literature and of course, Margaret Atwood.

In this interview, Esoterica’s Leah Eichler chats with Ivan Lesay, author of “The Topography of Pain,” his debut novel that was just translated into English and published by Guernica Editions. The book is written in fragments, keeping readers on their toes, and tackles issues such as sexual morals, ethics and capitalism in post-communist Slovakia. The interview covers Slovak literature after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Canadian literature and of course, Margaret Atwood.

Leah Eichler

Most books that catch our attention must have a beautiful cover or title. Although the saying goes: don’t judge a book by its cover, in practice this is not followed at all.

This book, however, has it all. An impressive cover, a title and even an annotation. After reading it, I have to say the story too, but there’s always that certain BUT…

The people, the food, the trees, the tables, we were patterns on the wallpaper, we were sticking to the cold wall of the universe. Grease dripped from the press, seeking the inferno to nourish the fires of hell, but hell was nowhere to be found, hell was the concept of our flattened world. (s. 296)

The Topography of Pain is the story of three different human destinies that are connected by strong threads into one whole, even though they do not affect each other, they are influenced by…

The first part deals with Naďa and her re-evaluation of life. It is her body and she can do with it what she wants. She can sell herself, she can write about men, she can re-evaluate her future or in a sense stop her illness.

The second part is slightly less engaging and concerns Jaro, who has lost his illusions after the revolution. Depicting his decisions, which while not as fatal, have great power to develop or further the development of the others.

Man is by nature selfish, I certainly was. And there are times when you need to get out on dry land and not look behind you to see if others are being pulled down by high water. (s. 253)

The third part is already a glimpse into the future, where the author dropped his imagination the most and created a dystopian version of the world. At the same time, he adds a letter form to the plot, in which the main „hero“ explains his thought processes or even actions, at the same time giving a view of a world and functioning in which we, as a human race, cannot distinguish between what is real and what is not real. It is an intermingling of thought/fantasy with reality, of which you the reader become a part as you stop knowing, as does the main character, what is going on and what he is thinking.

I have to appreciate the fact that the book is really exceptionally written, full of philosophical thoughts, reflections on the past, present or future, on how we can control our body, but at the same time we lose power and will over it, it is full of secrets, family „pains“ that have an impact on the functioning not only in the circle of loved ones, but also in the whole society, on how the environment and the regime (or the country) have a great deal to do with how we function, how we think, how we act.

Don’t forget, he was telling Jaro, in civilization, regimes change, but people stay the same. (s. 182)

The writing style is full of foreign words, definitions, but also vulgarisms, which give the book a kind of „pizzazz“. The author bet on a vision of the future, a representation of the past, he combined everything in one book, in one family that had to jump over various obstacles, but at the same time it was not a kind of a template family either, because its members did not show interest in such a family.

The book was harder to read, it is saturated with information and ideas, which in turn takes away from its quality and makes it a mass that when you read it you don’t know how to evaluate it (although we can take these ideas as a positive, but that’s a matter of perspective).

The story unfolds against a backdrop of time-planes, fantasy and reality, a search for meaning in a life that is full of physical but mostly „psychological“ pain that we have to live with and experience.

„…I loved her, she was great, I didn’t deserve her… God, that’s bullshit… am I really just going to tell you this about her? I have a lot of memories of her, but when I think about it… it’s like I never got to know all of her.“

„Like she lived partly in another world,“ I knew exactly what you were talking about.

„Elusive,“ you said, and I nodded. (s. 297)

Of the three parts, I liked the first one the most, which kept to reality and did not drift into the realms of politics, the past or the distant future full of robots, a broken world or technological progress.

I went into the book expecting a simply complex story, but what I got was a vision that wasn’t „rosy“. Although the handling of the language was excellent, Topography of Pain did not win my heart or convince me. Obviously if I went into it with a clean slate and no expectations, my thoughts would have gone in a different direction.

It is worth reading, however, because it is an interesting probe into ideas that are more complexly expressed, yet so easy to understand as to be frightening. I can rate the book as „strange“, „magical“, a literary feat worthy of reflection, but I can’t help but think that sometimes less is more, and while the ideas were interesting, their over-saturation spoiled their „image“ considerably.

Life served few stories and even fewer points, mostly just fanned the flames into dead ends, into alleys without content, passages without meaning (p. 305).

>Sima<

Thanks to bux.sk for providing the book for review You can also buy the book on their website. To get a better idea of the plot, you can watch the video on youtube, just click here.

My relationship to Slovak literature is such that if a work of literature catches my attention or is approximately my genre, I like to give it a chance. So when the new Topography of Pain came to my attention as a Slovak novel with a hint of dystopia, I reached for it – or rather, I requested it from the publishing house Ikar, to whom I would like to thank very much. And although I didn’t like the book that much in the end, I find it interesting enough to briefly introduce it to you.

Three destinies, three maps of painful places. At the moment when her health betrays her, Naďa reassesses her relationship to herself, to her surroundings, and ultimately her moral principles. It’s her body, she can do whatever she wants with it. Jaro reassesses for different reasons, he lost his illusions after the revolution, but the consequences of his decisions are no less fatal. At the end of the intertwined stories stands Adam, who navigates the new, uncertain and changing world of the future with seeming ease, while gradually asking himself the same questions and seeking his own answers. (cover & annotation from bux.sk)

What you might want to know about the author:

-> Ivan Lesay is, among others, a political scientist and economist who currently works in the field of European finance. From 2015 to 2017, he served as State Secretary of the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic and received the President of the Slovak Republic Award for Young Scientists.

-> He is the author of several professional publications and in 2012, together with Joachim Becker, he published the popularization publication Life on Credit (Everything you wanted to know about the crisis).

-> In 2016, his fairytale book A-KO-ŽE was published.

-> He also writes lyrics for the hardcore-metal band Fishartcollection.

-> About his latest novel, Topography of Pain, he says that in it he tries to „map the impact of historical events on the lives of individuals“ and that it is „a book about Slovakia, about Czecho-Slovakia, about Europe“.

What you should know about the book:

-> The book tells three stories of representatives of three generations of one dysfunctional family. In the first part, we follow young Naďa, who is currently struggling with a serious illness and begins to earn money through prostitution. In the second part, we follow her father Jaro at the turn of the 90s. In the third part, the aforementioned „dystopian tinge“ appears as we look into the near future with Naďa’s cynical son Adam.

-> The book is full of unmarked time-jumping, flowery descriptions, and convoluted musings that make it a difficult, slow read.

-> Besides, it’s really very open, you’ll find a lot of sex and swearing in it.

-> The Topography of Pain offers an interesting, unembellished look at the nature of individuals and society, but the way it’s handled doesn’t suit everyone – I’d say you have to tune into a certain wavelength, which I didn’t.

I recently introduced you to the versatile author Ivan Lesay and told you a bit about his new novel Topography of Pain. Today, we take a closer look at the book.

„Three destinies, three maps of painful places.“

Map 1: Slovakia, present. Naďa lives an ordinary, but at the same time very empty life of a college student. But when she falls seriously ill, she begins to re-evaluate her previous relationships and principles and takes an unexpected path – the path of prostitution.

Map 2: Czechoslovakia, turn of the 1980s and 1990s. Naďa’s father Jaro collects his shattered post-revolutionary illusions and makes a number of unfortunate decisions that will affect his family as well.

Map 3: The Future. Naďa’s son Adam grows up abandoned in a bizarre world full of technology and cruelty, and thrives in it thanks to his own cynicism and callousness. Until suddenly…

The book gradually presents three perspectives of representatives of three generations of one family, which complement each other. Each is divided not into chapters but into unmarked smaller sections arranged without any chronology. Thus, in practice, one begins to read the three times and often gropes.

However, even if the story didn’t jump around in time so much, it wouldn’t be an easy, relaxing read. The writing style itself is too experimental and idiosyncratic for that. Brutally honest, unadorned images (often full of sex and accompanied by lots of swearing) are interspersed with strange, almost poetic images, and various musings. These can be considered profound or perhaps pseudo-deep – depending on how much the book and its treatment suits you.

I probably liked best the depiction of our familiar Slovak society throughout history, whether an extra look at a revolutionary period not very familiar to me, a depiction of „today“ without unnecessary illusions, or a colourful, disturbing vision of the future. Exploring the dystopian world through Adam was definitely what I enjoyed most, except that along with that part came an ending that I found unnecessarily confusing and full of unfinished hints.

The author really excels at portraying imperfect, not exactly likable, yet very realistic and human characters. His science-writing perspective on the workings of society is also interesting. It’s just that, overall, the book pushes the saw a little too hard for me with everything, and I found myself rather lost in what was supposed to be unique, profound, original and thought-provoking, and I’m not even sure what the work was trying to tell me. Maybe the fault is also on my side – but certainly not only there.

I believe that The Topography of Pain will find its readers who will gratefully immerse themselves in such an artistic treatment of an unpleasant reality, and who will readily ponder with the author over individuals and society from all sides. So, if the novel intrigues you in any way, feel free to give it a chance. However, I prefer a more straightforward writing style, a clearer plot and less depressing stories, so in this case I was reaching completely beside the mark – which is why I chose not to rate the book with stars.

What was the last book you said to yourself – so this was a hit next door? And no, The Last Gentleman doesn’t count, we’ve already discussed that.

Remember how I had to use annotation for the Black Lies mini-review because I didn’t know any better way to describe it? Well, now I’m going to use it for different reasons:

Three destinies, three maps of painful places. At the moment when her health betrays her, Naďa reassesses her relationship to herself, to her surroundings, and ultimately her moral principles. It’s her body, she can do whatever she wants with it. Jaro reassesses for different reasons, he lost his illusions after the revolution, but the consequences of his decisions are no less fatal. At the end of the intertwined stories stands Adam, who navigates the new, uncertain and shifting world of the future with seeming ease, all the while gradually asking himself the same questions and searching for his own answers.

I’d like to agree that this is exactly what I found in the book, but I couldn’t get caught up in the thought processes of the main characters. As they say, a hundred people, a hundred tastes, every book was written for a certain reader, but to be honest, I can’t compare this book to any I’ve read so far to bring it closer to you. I’ve probably read mega few of them. For most of the story, I felt like the main characters were trying to retell the fantas(wilds) they dreamed up when they could unconventionally break free from the chains of reality, but they were dispensing them in sequence after sequence that if they didn’t understand them, I didn’t either. I have to admit that I don’t regret reading it, because the author uses an admirable hit parade of words, so my vocabulary smiled, and if I’m to take anything away from the book, it’s definitely to catch a bit of wordplay with no rules. For example, I saved in my notes, „He looks defiantly at the unknown figure in the suspected coordinates“ or „We all stamp our apologies with shards of the past.“ Or the tip of the iceberg (no irony, a really nice thought) – „Time is a convincing one-way illusion, though; you can’t back up in it.“ It’s three stories, and with each successive one, I was hoping to be caught up. But once I started to catch on, the author very quickly disabused me of my error. Here and there the stories came to me as poems, poetry translated into a novel. The text, however, comes across so sovereignly that I won’t allow myself much criticism, but I do admire the proofreader (again, don’t look for irony) for being able to discern what is a blunder of authorial blindness and what is intent. In the end, all three characters struck me as similar in at least some ways. I didn’t understand a single one, and I think I was a conscientious listener. Overall, my expanded vocabulary would describe the book as an inventive chaos (in places inaccessible to the weaker natures) combined with clusters of words pasted on paper like a makeshift amphitheater, but… what was the purpose of the play? The book caught my attention because of the title, at first I was expecting something psychological about pain in the true sense of the word, but at least from a marketing point of view it was a great move. If you’re not looking for a typical story and really want a challenge, then shamelessly treat yourself to The Topography of Pain. After all, I made it to the end too.

The book can be found on Bux.sk – https://www.bux.sk/knihy/562883-topografia-bolesti.html and I thank you for the review copy.

I have friends who live where the author lives, and since it’s a small community, I got my hands on this book. I have to admit that I had some preconceived notions about it, hence the book could only surprise me. And believe-it-not, it succeeded. Pleasantly. Though at first I was bothered by the wordy sentences, and a few stylistic mistakes that maybe didn’t make sense only to me, but later on the real power of literature and a bit of poetry and a lot of insights were demonstrated, which I found really apt. The last part of the book is a sort of science fiction, which is not, on the whole, appealing to me PERSONALLY, so I didn’t enjoy it all that much. However, it definitely deserves to be rated higher, so I’ll try to tweak the rating so that I think it’s fair, though I’ll have to give it a higher grade on purpose. That’s the toll of being only the second reviewer.

bat 088